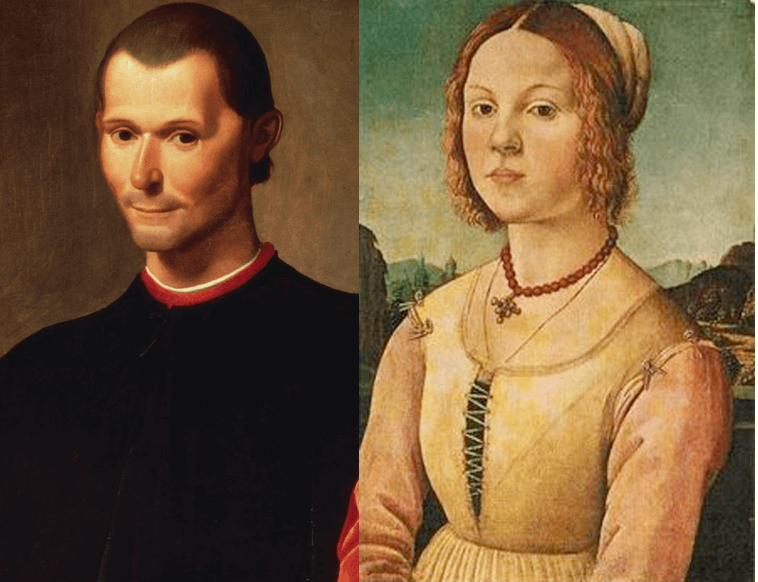

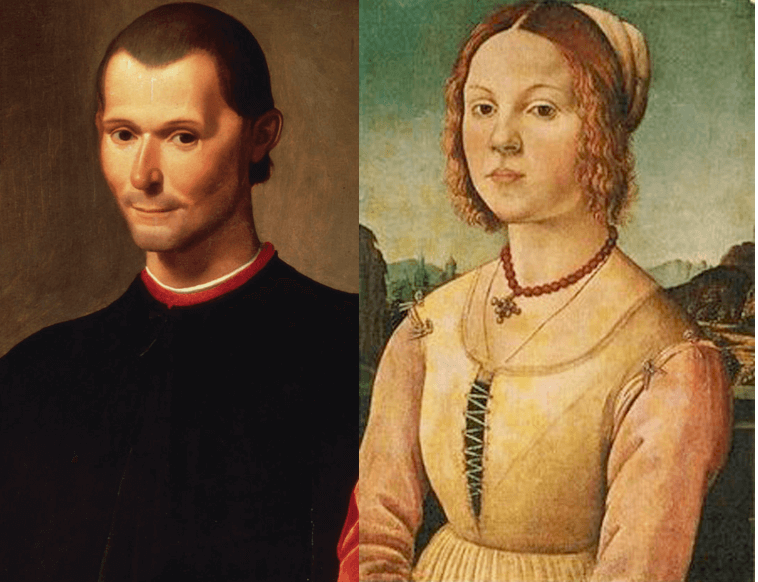

Machiavelli and his wife

In June 1502, a young Niccolo Machiavelli, is dispatched from Florence to negotiate with the thuggish Cesare Borgia who has just scandalised Italy by invading the state of Urbino. History will report their meeting, but say nothing about the leaving of his new young wife in their house on the south side of the Arno.

And yet it must have happened…

‘I should have known sooner. How can I get everything ready so fast?’

‘You knew as soon I did, Marietta. There is nothing to upset yourself over. I will not be away long.’

‘What do you mean? You may never come back!’

Through the open windows on the Via Guicciardini, there is the muted rubble of carts as the city closes up for the night.

‘What if this Borgia monster kills you or takes you hostage?’

‘Wife, you have no understanding of such things. Nothing will happen to me. My fellow diplomat is Bishop Soderini.’

‘A bishop? That won’t stop him. They say that the Pope poisons bishops and cardinals every day to get his hands on their money.’

‘You listen to too much street talk,’ he says laughing.

‘Well, what else is there to do? My husband is never here and when he is he never tells me anything,’ she mutters with a touch of petulance in her voice; their marriage is young enough to accommodate a little sparing.

‘The city is in crisis. I have been working.’

‘Where? In the ale house?’

‘It is your own vinegar and rosemary that you can smell on my breath.’

‘Yes, that’s what I mean.’

While she is no great beauty, when her spirit is up her eyes glint and her cheeks flush. Some weeks before, an early pregnancy had been washed away in a blood tide, and though she had coped well enough – a woman’s life, she had informed him, is full of such wounds which men can never comprehend – it is clear that this news of his has upset her more than she would chose to show. He should be more solicitous, but the anticipation of his journey has wiped such matters from his mind.

‘Well, I have done my best with your shirts,’ she says looking up from the bundle of clothes on the table. ‘See – these two have new collars and there is a change of doublets, both clean and pressed. Of course it’s not enough. But at least this way if this godless Duke sticks a knife in your back it is only old velvet he’ll be ruining – and before you say again that nothing will happen to you, what about those brothers that were fished out of the river in Rome? That wasn’t street gossip. They were the rulers of… well… wherever it was –‘

‘Faenza. But they no longer ruled. The city was in Borgia hands. Their death was inevitable.’

‘Niccolò!’

‘What? You want me to talk to you about what is happening. No duke can afford to have rival families left for opposition to graft itself onto. I am telling you how men are, Marietta, not how you might like them to be.’

‘Then you all are equally godless and if only women kept their legs closed there would be fewer of you,’ she says, primly committed in her disapproval. ‘Sometimes I think I should have married that apothecary from Impruneta. He had a good business you know. And I could have been of use to him.’

‘What, making rat poisons and poultices for old men’s gout? You would have shrivelled up with boredom.’

She grunts. The truth is Marietta Machiavelli is not sure how far her husband’s unorthodox views offend her, for just as he seems to enjoy voicing what others might think but never say, so she has found a role being the foil for them. It is better to have him talking than always living in his head. And not just in his own. There have been dinners where the table has felt crowded and there is no one but the two of them sitting there.

She pushes the last of his clothes down into the small travelling bag, ties a leather belt over it and drops the bag onto the floor where it hits a metal cooking pan, waking the dog, whose bark then disturbs the goose so that the house is suddenly full of yapping and honking.

He laughs. He would give odds against any robber who tried his luck while he was away. If she had her own troops Cesare Borgia would probably be buying his wife into his service. Marriage. When he has the time to think about it he would probably say that he could have done worse. God knows he could not have borne a stupid or docile wife.

‘Here,’ she says holding out something in her hand. ‘Perhaps you will do me the favour, husband to wife, of wearing this?’

‘What is it?

‘The badge of St Anthony. Attach it prominently to your hat when you are on the road.’

‘Marietta! I am not a pilgrim –‘

‘Would that you were! Then the Saint will protect you.’

‘What? Even from a godless prince?’

This extract from In The Name of the Family: A Novel of Machiavelli and the Borgias